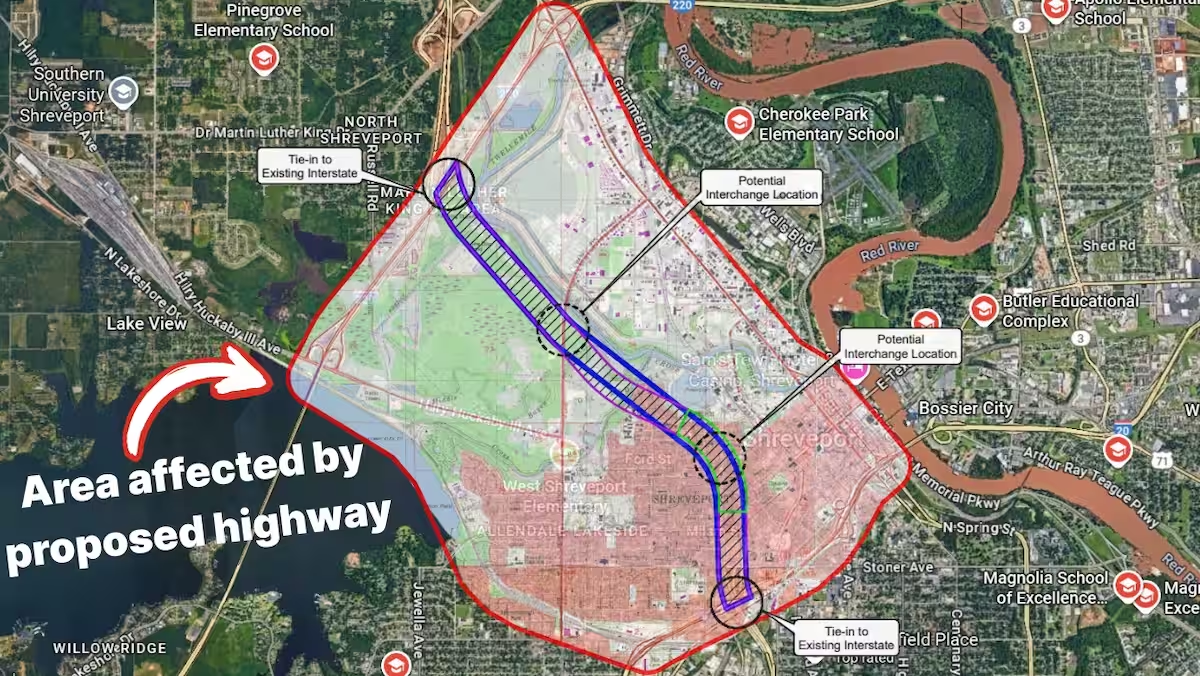

In Shreveport, Louisiana, a deeply controversial project aims to fill a 3.5-mile gap in Interstate 49 by building a new highway directly through the city’s core. The I-49 Inner City Connector (ICC) would connect the existing I-49 segments at I-20 and I-220. It is an uncompleted remnant of the original Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956.

Supporters describe it as the "missing link" in a national corridor stretching from New Orleans to Kansas City. But, in practice, this project is not about solving any real transportation problem. It is a textbook example of the broken federal funding system driving marginal, costly, and destructive local investments simply because the money is available and there was once a line on paper.

An Interstate Project in Search of a Purpose

Estimates in 2022 place the project’s cost at $900 million, with some alternative scenarios reaching higher. That money is being marshaled not to address traffic congestion — which is minimal and easily managed by existing routes — but because it can be matched with federal funds.

Through traffic, the kind this project is ostensibly designed to serve, amounts to just 235 vehicles per day — barely more than one every six minutes. That’s fewer vehicles than seen in many alleyways in larger cities. The logic is clear: If we can get Washington to pay for it, we have to say yes.

The economic justification for the ICC is built on a shaky foundation of manipulated forecasts and economic distortions. According to the official study required to receive federal funding, the average driver will save 3.2 minutes per trip — a benefit translated into $0.53 per day per commuter. These negligible savings are then aggregated across decades and inflated into claims of millions in annual economic benefit. This isn’t real value; it’s a manufactured narrative dressed up in data.

The same study estimates over 30,000 new jobs, many in retail, driven by highway-adjacent development. But Shreveport has a shrinking population, stagnant wages, and no plausible pathway to support that level of new growth. In truth, these are not new jobs, but displaced ones — shifted from one part of town to another as older businesses are closed and reopened near the new corridor. It is the very definition of a low-return, subsidy-driven shift in the development pattern.

This project persists because of the structure of federal incentives. When a segment like the I-49 Inner City Connector appears on the original interstate map, it acquires a sense of inevitability that overrides present-day needs and logic. Even though the interstate system was declared complete decades ago, a few costly and difficult segments remain. These are not vital infrastructure gaps but bureaucratic leftovers from a previous era.

Projects like the ICC endure because their existence opens the door to federal funding. The presence of federal expansion dollars distorts local decision-making: States are incentivized to chase what can be funded, not what is prudent. Instead of focusing on maintenance or locally beneficial investments, states are pressured to redirect resources toward match-eligible projects — however marginal or damaging they may be.

This is not a product of clear public need or strategic planning. It is institutional inertia disguised as progress. The presence of a line on a decades-old map does not make a project viable. It does not mean a need still exists, nor that a community should be sacrificed to fulfill a bureaucratic blueprint. Yet in the eyes of transportation agencies and federal funders, that line is reason enough.

A Community Forced To Pay the Price

The local impact of the I-49 Inner City Connector has been severe and multifaceted. First, Louisiana lawmakers chose to divert $100 million from urgent maintenance needs — including the structurally deficient Jimmie Davis Bridge — in order to secure a federal match for this expansion project. That decision reflects a distorted set of priorities, driven by a funding system that rewards expansion over stewardship.

Second, the promise of federal dollars has mobilized a segment of the local business community and land speculators. These interests view the project not as a transportation investment, but as a chance for federal transportation spending to tilt the local market in their favor.

Public infrastructure spending on this scale has the power to inflate land values, redirect commercial activity, and anchor future development — creating clear financial winners. But, in a place like Shreveport, for every government-backed success story, there is a competitor left behind: local businesses pushed out, disinvested districts bypassed, and entrepreneurs who must now compete on a tilted playing field shaped by political alignment with a billion-dollar investment instead of merit.

Finally, the mere existence of this project as a looming possibility has depressed investment in the Allendale neighborhood for decades. With the specter of demolition hanging over their heads, residents and businesses have lived in uncertainty, unable to confidently invest in their homes or communities. Allendale has been effectively held in limbo, sacrificed not by bulldozers, but by policy neglect and institutional ambivalence.

The ICC should be seen clearly for what it is: a billion-dollar instrument of market distortion. It does not solve a transportation problem — because there isn’t one. What it does is redirect public resources to a handful of well-positioned beneficiaries while putting their competitors at a structural disadvantage.

A Case Study in Systemic Failure

The I-49 ICC is not an anomaly — it is a case study in how federal transportation policy creates distorted incentives and poor outcomes. At nearly $1 billion, this project represents a staggering misallocation of resources in a state with pressing transportation needs.

Louisiana has a $19 billion backlog of repair and maintenance work, including structurally deficient bridges, neglected rural highways, and aging urban infrastructure. Redirecting scarce public resources to an unnecessary expansion project not only defies logic — it undermines the public trust.

Yet projects like the ICC persist because access to federal dollars — not local need or strategic merit — drives decision-making. The presence of matching funds can turn a politically motivated idea into a financial inevitability. And once a project of this scale is in play, it attracts private interests eager to benefit from public spending, even if that means tilting the market and displacing competition.

Consultants, contractors, and lobbyists profit from this expansion-first approach, while the technical professions have been reduced to producing justifications, rather than solutions. Local governments, desperate for economic activity, are pressured to pursue what is fundable, even at the cost of their own long-term resilience.

To change this trajectory, we must fundamentally reform the way we fund transportation in America:

- End the use of federal interstate-era programs to fund marginal expansion projects.

- Prioritize system maintenance and repair over expansion.

- Remove incentives that reward politically engineered proposals over practical investments.

- Equip local governments to make bottom-up decisions that reflect community priorities and long-term value.

Until that happens, cities like Shreveport will continue to face projects like the ICC — not because they make sense, but because they are made fundable.

Federal Policy Is Distorting Local Markets

The I-49 Connector is not a transportation solution. It is a $1 billion market intervention — one that advances not to solve real mobility challenges, but because it meets the procedural and funding criteria of an outdated federal program. By using public dollars to shape private outcomes, it distorts local real estate markets, privileges politically connected developers, and sidelines competitors who must operate without those advantages.

The project doesn't just misallocate resources; it also suppresses productive investment, redirects growth based on artificial incentives, and signals to cities that chasing federal funds is more important than meeting local needs. Until these structural incentives change, federal transportation policy will continue to produce more distortion than value.