The I-10 overpass slicing through New Orleans’ Tremé neighborhood isn’t just concrete—it’s a scar.

Before construction began in 1966, Claiborne Avenue was a thriving corridor, flanked on either side by hundreds of oak trees. Families lived above corner stores and restaurants. “There was a grocery store, a linen shop, a hardware store, and a restaurant on the [block],” one resident recalled. Within walking distance: a movie theater, three pharmacies, and the smell of coffee beans ground fresh each day.

All of it changed on Ash Wednesday, 1966, when bulldozers uprooted the oaks and began erecting concrete columns. Over the following years, hundreds of homes and businesses were demolished to make way for the elevated highway—an estimated 500,000 square feet or more of residential and commercial life erased. Hundreds of families were displaced. In just two decades, generations of history were uprooted, much of it in Tremé, which was literally bisected by the overpass—an intrusion locals came to call “The Monster.”

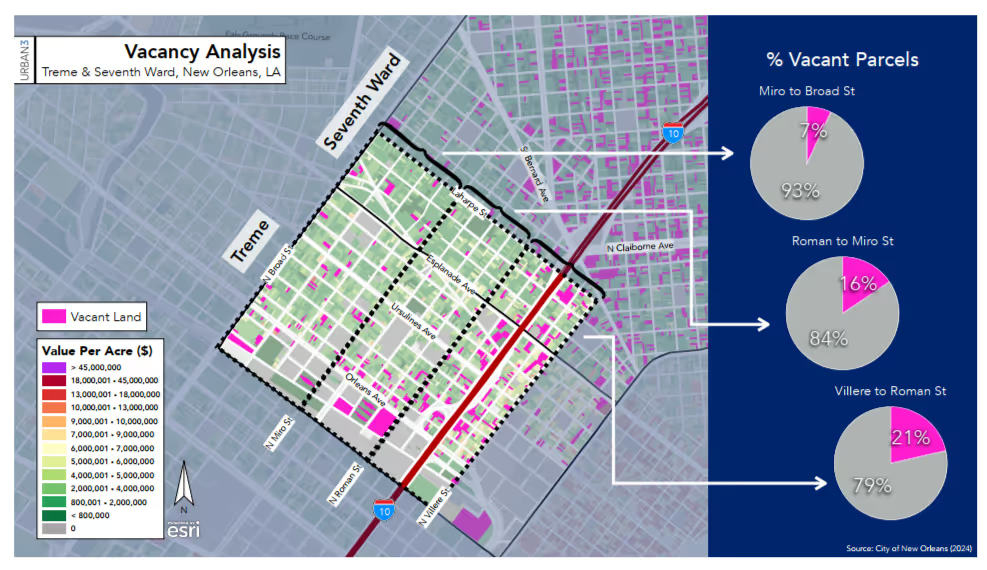

The damage isn’t just historical; it’s measurable. Today, the blocks closest to the expressway are pockmarked by vacant lots, underused industrial buildings, and properties that have lost much of their value. Once a dense neighborhood humming with commerce and culture, Tremé now carries the economic fallout of a highway that sliced through its core.

A Loop of Disinvestment

Long before the expressway, the groundwork for its consequences had already been laid. In the 1930s and 1940s, Tremé and the adjacent 7th Ward were redlined—deemed “hazardous” by federal housing authorities, and systematically denied investment. That label shut residents out of mortgages, starved the area of capital, and signaled to both public and private sectors that disinvestment was acceptable. By the time the Claiborne Expressway was proposed, Tremé had already been pushed to the margins.

The highway was pitched as progress, but in this neighborhood, it acted more like a final blow. Tremé was never given the chance to recover—let alone thrive—with six lanes of concrete overhead.

Urban3 compared Tremé’s economic performance to nearby neighborhoods untouched by the interstate. Their modeling suggests that more than a billion dollars in property value was never realized. Nearly a thousand parcels—homes, businesses, gathering places—were erased to make way for a road that today costs the city an estimated $4.7 million a year in lost property tax revenue (adjusted for 2024 dollars). Besides what was torn down, there’s the impact of what never took root: the homes that were never built, the businesses that were never opened, and the generational wealth that was never given the chance to grow or get passed down.

The long-term damage is visible in the business records too: in 1960, there were 132 registered businesses along Claiborne. By 2000, that number had fallen to just 35.

Living in the Shadow of “The Monster”

The impact of the highway isn’t only visible in missing tax revenue. It reverberates in the daily life of people who still call Tremé home.

For planner, artist and frequent Strong Towns guest, Amy Stelly, the overpass isn’t just as an eyesore, it’s an environmental and sensory assault. In an EPA-funded study commissioned by Stelly, researchers measured both sound and air quality beneath the expressway. The findings were stark. Noise levels under the Claiborne overpass could cause permanent hearing damage after just an hour of exposure. And pollution levels—roughly 18 micrograms per cubic meter—far exceeded federal guidelines. “It should be at most—at most—12,” said graduate student researcher Beatrice Duah. “So it is way over the limits.”

Noise isn’t the only intrusion. There’s debris. There’s soot. There are all kinds of things that fall from the deck of the expressway.

Yet, beneath that structure sits a small playground, its equipment mostly unused. The reason, Stelly says, is simple: “Because kids are smart. It’s the adults who aren’t. It’s the adults who built the playground under the interstate.”

The result is a space meant for children, hollowed out by the constant presence of traffic overhead–nearly 115,000 vehicles a day, according to a 2012 study. The noise makes it hard to hold a conversation, let alone play. “I have never seen a child play here,” Stelly said.

On paper, it was an attempt to reclaim space for the community. In practice, it became another symbol of what had been lost.

What Comes Next

While Urban3’s modeling is based on projections, the story it tells is grounded in real consequences. For many residents, any alternative to the overpass would be an improvement. “Removal is the only cure,” Stelly is convinced. “I’m insisting on it because I’m a resident of the neighborhood and I live with this every day—the science tells us there’s no other way.”

In 2021, federal leaders announced a new effort to undo the harms of past infrastructure decisions. The Reconnecting Communities program was billed as the first of its kind—a chance to repair the damage left by highways that cut through once-thriving neighborhoods. The Claiborne Expressway became a favorite example in federal presentations—a well-worn symbol of what had gone wrong. And with the structure itself aging out of service, it was the perfect candidate for a bold fix.

For a moment, it seemed like the stars might align for Tremé.

Stelly led a proposal to remove the overpass and rebuild Claiborne Avenue as a walkable, neighborhood-scale street. But when the first round of funding was awarded, her vision was passed up. Instead, the Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development (LaDOTD)—the same agency responsible for maintaining the expressway–received the award. While the agency didn’t receive their requested $100 million, the $500,000 they secured was earmarked for studying “connectivity improvements.”

Despite being held up as a national symbol of infrastructure gone wrong, the expressway stayed exactly where it was. What the community asked for was transformation. What it got was more study.

This isn’t repair. It’s avoidance. All across the country, projects pitched as “reconnection” end up pouring money into the space beneath or above the highway, extending the lease of the structure responsible for the wounds to begin with. Decorative crosswalks, lighting upgrades, public art, and weekend vendor stalls may improve appearances, but they leave the core harm unaddressed. As Stelly put it, “It’s lipstick on a pig.”

It’s not too late to choose differently. A highway that was built in the name of progress can be removed in the name of healing. But only if we’re honest about what’s broken—and brave enough to dismantle it.