Last week, I wrote about Jeff Siegler’s strong stance that downtown ground floors should never be used as residences. He is right to highlight what is at stake: the loss of public life when storefronts close themselves off. But Strong Towns thinking points us toward a different conclusion. Places are not static; they are dynamic. And sometimes, “for-awhile” uses can be the bridge that gets us from stagnation to vibrancy.

Principle 1: Plans Cannot Substitute for Present Action

The Motiva story in Port Arthur, which I discussed last week, makes it clear that plans are not a substitute for action. A regulation meant to prepare for an imagined future prevented the city from seizing a real opportunity in the present. Staff clung to their plan, saying they needed to ensure nobody accused them of neglecting each site’s parking when the “full build-out” occurred seventy years out. But the reality was that no such future was coming. Downtown needed people and energy today.

The Strong Towns approach is built on the understanding that places are not “now and forever” systems, but “for-awhile” systems. They evolve in fluid response to local need, shifting incrementally as conditions change. A ground-floor space downtown that houses residents today might host a grocer tomorrow, and then a café or bookstore later. The expectation is not permanence, but adaptability. Good planning supports small wins that generate momentum in the present and leaves space for the next evolution to emerge, rather than freezing possibilities in place while waiting for a perfectly imagined future.

Principle 2: Flexibility Is a Better Bet Than Certainty

The second lesson is that flexibility is always a better bet than certainty. Parking minimums, density caps, and rigid use requirements all come from the same impulse: to secure a particular outcome far into the future. But that kind of certainty is impossible. Cities are living systems, not machines. The role of city codes should be to preserve adaptability, not to predict the future.

A Strong Towns approach says: let activity return, let buildings fill, and make sure the rules allow them to evolve as conditions change. It recognizes that the conditions of today are not the conditions of tomorrow. A building that serves as a home for six years may become a restaurant for twenty, then an office for a decade, and later return to housing. This fluidity is not a failure of planning — it is the very nature of resilient places. The goal is not to lock in certainty, but to make sure buildings and blocks remain flexible enough to host whatever use the community most needs at any given moment.

Consider these buildings. All three of them are at the edge of our village core; all three buildings served as homes in the first number of decades of their existence; two of these buildings now house businesses and residents.

Vancouver’s Joyce Station and the Displacement of a Vital Filipino Hub

In Vancouver’s Joyce Station neighborhood, a vibrant commercial cluster serving the Filipino community was threatened with erasure by redevelopment. As The Tyee reported, “The small cluster of businesses on Joyce Street around the SkyTrain station might not be the official consulate that Miemban-Ganata once worked for, but it might as well be an unofficial one.”

When redevelopment displaced these businesses, there were no adjacent properties available for them to use. The rigid separation of residential and commercial zones meant that adjacent buildings were ineligible for updated uses.

In the traditional development pattern, a Filipino grocer, restaurant, or corner store would almost certainly have approached nearby property owners — even residential property owners — to rent out their yard, a garage, or the main floor of a house. Those buildings were flexible shells, easily adapted to new uses.

Instead, the city insisted on the persistent segregation of retail from residential, even as city reports expressed dissatisfaction that the area had an “irregular land-use mix” and “weak commercial street frontage.”

“For-awhile” urbanism would see adjacent buildings as prime candidates within that irregular land-use mix for conversion into stores. This is so familiar that it hurts: the standards conflicted with the needs of a strong and resilient neighborhood.

Who suffered?

The grocer tried to relocate to an industrial park that was a considerable distance from the churches, immigrant services, and recreational spaces of the Filipino community that had been drawn to the neighborhood. The business, previously so vital, failed when its connection to the community was broken.

The other businesses were wiped out without being given a fighting chance to do what our ancestors would have done: figure out which property owner nearby could be convinced to work with them to make a new space available for them.

How did those little salons and flower shops and convenience stores end up in the front or attached to the side of homes in traditional neighborhoods? They needed space that worked for them and created it.

This is “for-awhile” urbanism, and it is a close cousin of fine-grained urbanism, which provides opportunities for the small fry to thrive even if it results in a…how do I put this politely…“irregular land-use mix.”

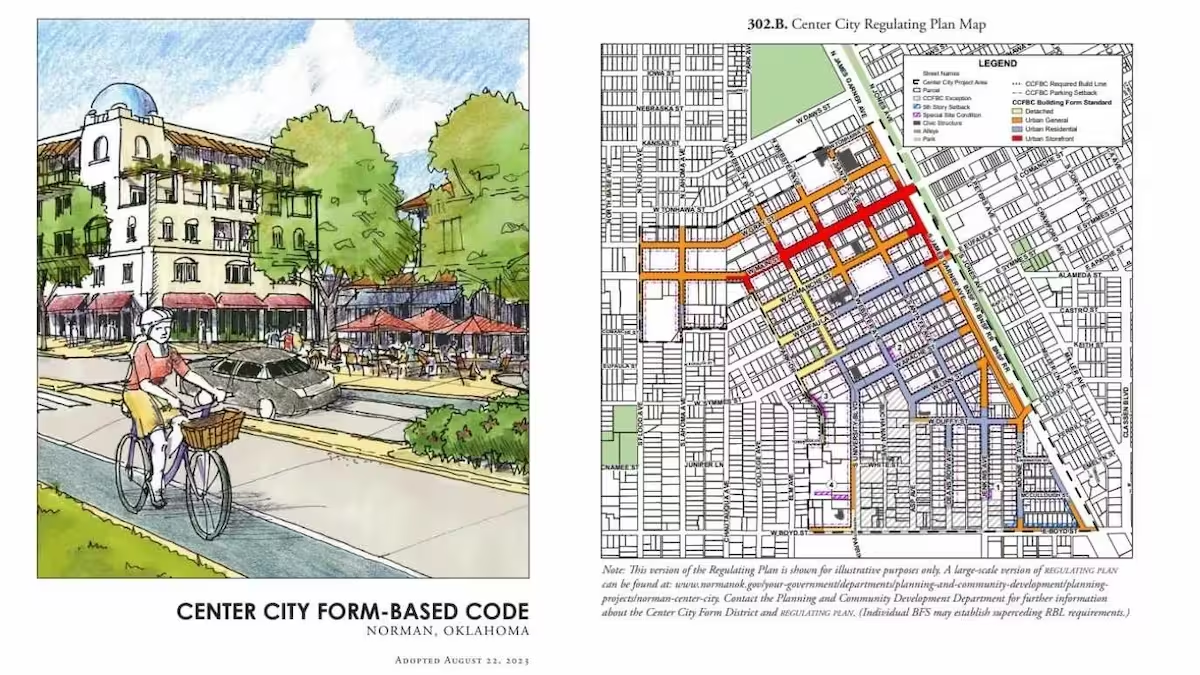

Form-based Foibles in Norman, Oklahoma

Norman, Oklahoma, home to the University of Oklahoma, offers another lesson. The city adopted a form-based code for its main street near campus, modeled on successful streets elsewhere. The code streamlined approvals by asking simple but important questions: Does this project face the street well? Does it improve livability?

Yet even with a simplified process, development lagged. The reason was simple: the code only allowed retail on the ground floor, and housing was not permitted there.

Developers, backed by market research into the conditions that are necessary for businesses to thrive, could not find ground-floor retail tenants for these areas undergoing redevelopment. The homes that were promised to boost businesses still needed to be built before there would be a critical mass of foot traffic and local customers. So banks refused to finance projects without signed commercial leases.

What the developers wanted to build — housing, especially for students and other Norman residents — was not allowed. The city, meanwhile, feared exactly what Jeff Siegler described: “Shhh, baby sleeping” signs replacing the storefront vibrancy they hoped to encourage. The result was very little uptake, despite a code that was otherwise easier and more flexible.

The answer is not to forbid housing on the ground floor. The answer is to make those spaces adaptable shells. Build them so they can function as residences today, but easily convert to retail, offices, or studios tomorrow.

If we can turn warehouses into lofts and barns into “barndominiums,” surely we can design ground-floor homes that become coffee shops or barbershops when conditions change.

Beyond “Stacked Segregated Uses”

Too often, we call projects and areas like this “mixed use,” but what we really have is stacked segregated uses: retail on the bottom, housing on top, and never the two shall meet. I recognize that the phrase “mixed use” has utility as a planning term, but we should nudge the concept toward adaptability. Mixed use should mean a fluidity of allowable uses. It should mean a building can shift between uses as needs and opportunities arise. That is what makes places resilient.

Never Say Never

Allowing flexibility does not mean ignoring safety. Any new use must meet building codes. And if an activity becomes a nuisance, the city must step in. But that is a different challenge than freezing blocks in a dream-state plan that leaves storefronts empty.

Should someone expect to live for sixty years in a ground-floor unit in the heart of downtown? Probably not. But could it make sense for someone to live there for six years until a business owner offers to buy them out, or until the market supports a café or bookstore? Absolutely.

Siegler is right: the ground floor is the living room of the city. We cannot afford to lose it.

But like any living room, its value is not in sitting empty while we wait for perfection. Its value is in being filled with life, even if that life evolves over time.

.webp)