When cities talk about the housing crisis, the conversation almost always drifts toward policy. Debate bounces between zoning codes and comprehensive plans and then circles back to political will. We argue about whether regulations are too strict or not strict enough, whether developers are greedy or the government is incompetent.

But on the ground, much of the housing we say we want isn’t being blocked by bad policy. It’s being blocked by something harder to see: the everyday processes cities use to review and approve small projects.

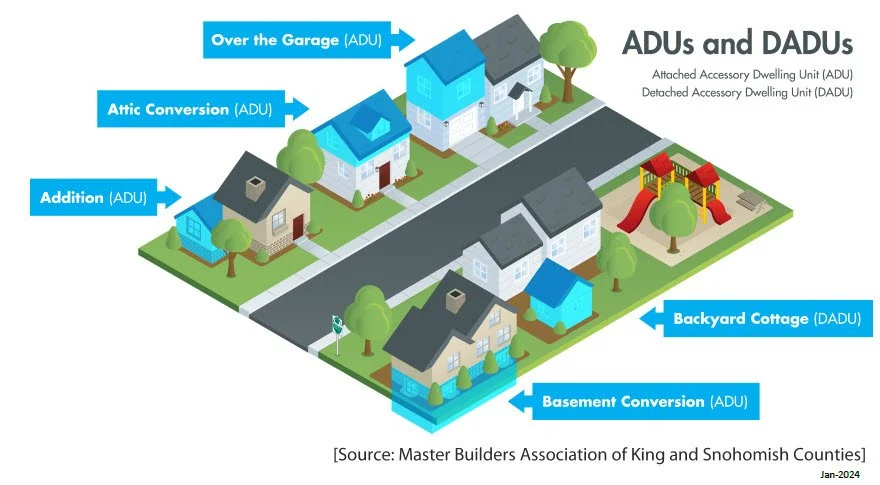

In more and more places, the rules technically allow incremental housing. Backyard cottages, accessory dwelling units, and small infill homes are legal on paper; beautiful, glossy images of these homes are shared on city websites and included in planning documents. Yet these homes rarely get built—not because of public opposition or failed rezonings, but because routine procedures treat small homes like major developments.

What we have is not a failure of vision, but one of process.

Where Housing Actually Gets Killed

Most housing does not die in a city council chamber or with a vote. It dies much earlier, inside city hall.

It dies during plan review, where approvals are structured as check-the-box exercises and often assigned to the newest or least experienced staff member. These reviewers are not empowered to interpret intent or apply judgment. Their role is to ensure strict compliance with standards written for very different kinds of projects.

It dies in departmental silos, where each division reviews a proposal through the narrow lens of its own manuals and procedures. It dies in the field, where inspectors and technicians are expected to enforce rules exactly as written, regardless of context—or even what was previously approved.

None of this is malicious, it’s simply the expected outcome of a system optimized for control. Nevertheless, the cumulative effect is devastating for small-scale housing.

When Big-Project Rules Meet Small Housing

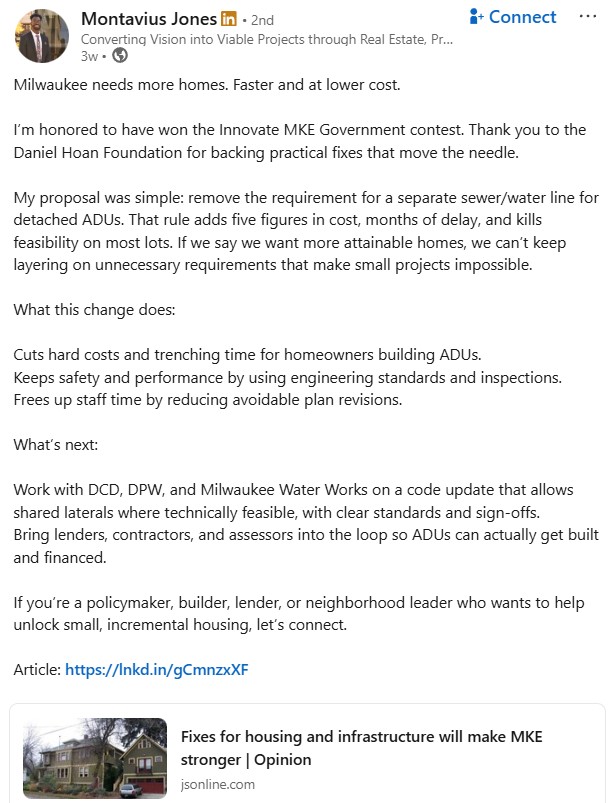

Milwaukee-based place-maker Montavius Jones captured this problem while discussing accessory dwelling units.

“If we say we want more attainable homes,” he wrote, “we can’t keep layering on unnecessary requirements that make small projects impossible.”

Jones had just won the Innovate Milwaukee Government contest for a proposal that was, by his own description, simple: remove the requirement for separate sewer and water connections for detached ADUs. That single rule, he noted, “adds five figures in cost, months of delay, and kills feasibility on most lots.”

This example is not unique to Milwaukee. In many cities, modest detached ADUs are required to install entirely separate sewer and water lines, as if they were standalone developments on undeveloped land. From a system perspective, the additional demand created by a small one-bedroom backyard cottage is marginal—often no greater than a basement apartment or home addition. Yet the response is maximal.

Those same additions and interior conversions are routinely approved through a basic building permit and inspection. The only thing that changes is the classification. Attach the unit to the house and it proceeds as a renovation. Detach it and move it twenty feet into the backyard, and suddenly it triggers an entirely different—and far more expensive—set of procedures.

Of course, these procedures did not come from nowhere. Utility departments and other technical divisions are system managers. They are responsible for maintaining complex infrastructure with limited staff and constrained budgets. Over time, they adopt one-size-fits-all standards because those standards reduce uncertainty. They prevent past mistakes from recurring. They make review faster for the reviewer and enforcement simpler.

That approach works when cities are building big things quickly. That approach scales up. But, it breaks down when applied to small, incremental projects. It cannot scale down.

When the same procedures are applied to a single backyard cottage or a small infill starter home, the result is not careful risk management. It is stifling overkill. At best, the project becomes unnecessarily expensive. More often, it simply never gets built.

It’s Time To Ask Better Questions

Cities do not need sweeping new housing strategies to fix this problem. They do not need to cut corners or abandon standards and oversight. What they need is a sense of proportionality.

They can begin by asking better questions of their own processes: Does this rule meaningfully protect the public, or is it simply familiar? Is the cost imposed proportional to the impact of the project? Are we managing real risk, or defaulting to category-based procedure?

In the case of small backyard cottages, the fix is straightforward. Treat them the way cities already treat additions and interior conversions. Allow connections to existing utility infrastructure. Empower building officials to verify work through the standard permit process. This isn’t a call for deregulation in the slightest. It’s a call for common sense.

Save complexity for complex projects. Match regulation to scale. And allow small homes to do what they have always done best: modestly add up to something meaningful over time.

Many of the processes cities rely on today were developed during eras of rapid, large-scale growth. They are designed to manage big bets: subdivisions, massive apartment buildings, and major infrastructure extensions. Those tools make sense when a city is deciding whether to underwrite growth that could strain budgets and systems for decades, but time and time again we see how they constrain the smallest projects.

Cities invest in technically trained staff, then design systems that prevent those staff from exercising discretion. That decision-making is instead pushed upward, bogging down elected officials and discouraging innovation where it is most needed. We don’t have a capacity problem, but we do have a problem of elevating procedure over judgment. If your place has already adopted the policies that will make it housing-ready, it’s time to look at the processes that stand in the way.

.webp)