Editor’s Note: This piece comes from a Strong Towns Local Conversation member observing how winter snow reveals the underlying priorities of our streets. The goal is not to prescribe a universal fix, but to encourage locally grounded reflection on how street design affects mobility and access year-round.

[[divider]]

Every winter, the same pattern appears. Snow falls, plows roll out, and crews work continuously until roads are mostly clear. Cars continue to move with minimal interruption.

At the same time, sidewalks disappear for long stretches. Crosswalks end abruptly as snowbanks pile up. Curb ramps—the places where people are meant to cross—become blocked or unusable. For many residents, this isn’t just an inconvenience; it’s an accessibility nightmare. People using wheelchairs, walkers, or strollers can find entire routes suddenly impassable because the infrastructure they rely on is treated as secondary.

This isn’t a failure of effort or goodwill. It’s not about who did or didn’t shovel. Winter simply reveals what our public right-of-way is designed to prioritize

Snow is a roadway audit, if you know where to look.

Roads Are Treated as Essential Infrastructure. Sidewalks Are Treated as Optional Space.

When snow falls, roads are cleared first, fastest, and most thoroughly. This makes sense within the logic of the system: roads are wide, continuous surfaces designed to be serviced by large equipment.

Sidewalks, by contrast, are narrow, fragmented, and often physically separated from the roadway. Even where they are publicly owned, they rely on different tools, different timelines, and sometimes different responsibilities. The result is predictable: sidewalks remain icy, narrowed, or blocked long after roads are fully passable.

What winter exposes is not neglect, but design intent. Roads are built to function year-round. Sidewalks are treated as “nice to have” left-over space once vehicle movement has been accommodated.

Intersections Tell the Most Honest Story

If you want to understand a street’s priorities, look at its intersections after a snowfall.

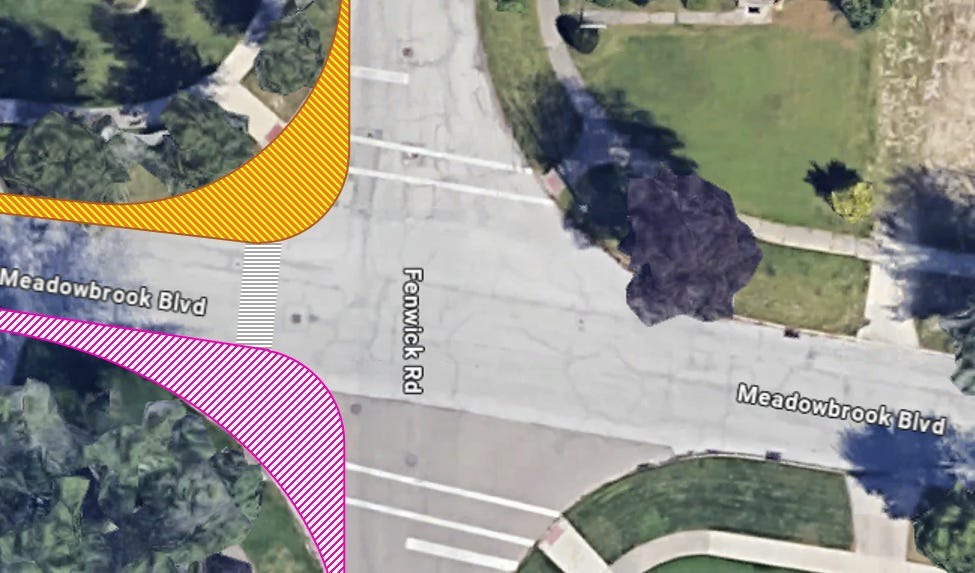

Pedestrians are forced to step into the roadway or detour away from the place where crossing is intended to happen because once the snow is off the roadway the job is “done”. People on foot are expected to navigate slush, ice, and piled snow at precisely the point of highest conflict.

None of this is accidental. Intersections are engineered first for vehicle movement and storage, with pedestrian crossings frequently constrained by what space remains. Winter strips away the appearance that all users are being accommodated equally.

On the other hand, one of winter’s lessons is just how adaptable vehicle movement is, even when streets are narrowed by snow. After a storm, lanes are often functionally slimmer. Shoulders disappear. Parking lanes vanish. And yet traffic continues to flow. Speeds adjust. Drivers, of course, adapt.

The extra asphalt that vehicles barely use in winter still dictates how far a person must walk across moving traffic in the summer. Crossing Warrensville Center Road at Fairmount Circle, for example, is a daunting 105 feet from curb to curb on a normal day! On a snowy day, that distance is reduced to less than 80 feet with a brand-new visual “refuge area” thanks to unplowed snow.

Winter unintentionally performs a kind of "road diet" and traffic survives it just fine. The fact that streets continue to function with less exposed pavement raises an uncomfortable question: why do we need so much of it the rest of the year?

What Winter Makes Impossible to Ignore

When the snow melts, these imbalances fade from view. Sidewalks widen again. Crosswalks reappear. The street looks neutral, even fair. But winter tells us several truths.

It shows us that our streets are not neutral spaces shared equally by all users. They are shaped by a set of design assumptions: that speed matters more than safety, that vehicle movement must be effortless in all conditions, and that walking can adapt around whatever space remains.

But it also reveals something hopeful alongside this imbalance. Vehicle travel continues even when lanes are narrowed, speeds are moderated, and excess pavement disappears beneath drifts.

This contrast is a place of opportunity. If we want streets that work year-round, for everyone who uses them, we can design them that way from the start. Not just by hoping for the best, but by learning from what winter “snows” us.

.webp)