When cities face growth, impact fees often feel like the responsible choice.

The public discussion usually starts something like this: a new development brings new residents, more traffic, and greater demand for public services. Roads, schools, pipes, and parks don’t build themselves. Someone has to pay for them. Asking growth to pay for growth sounds fair. It sounds prudent. And yet, many cities that rely heavily on impact fees still find themselves financially fragile. They struggle to maintain infrastructure, stretch operations thin, and quietly drift toward insolvency.

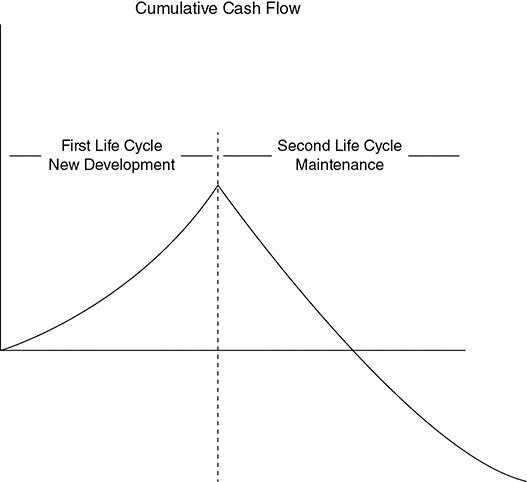

That's because impact fees are not wealth. They are a one-time cash payment—better understood as an entry fee into the local economy. In states that allow them, impact fees are established through detailed studies and formal processes. They are typically calculated by identifying a set of planned capital projects and spreading those costs across anticipated growth. Impact fees fund construction, but critically, they do not fund sustainability.

They make it possible to build infrastructure. Ribbons are cut. Photos are taken. The balance sheet looks temporarily healthier because a revenue source exists for construction. But the real costs—operations, maintenance, and eventual replacement—arrive much later. When they do, there is no second impact fee waiting to cover them.

This is where the illusion begins. Most municipal insolvency does not begin with reckless spending. It begins with deferred maintenance.

When the bill comes due

Consider a water or wastewater treatment plant that has served a community for decades. Its systems age gradually. Pumps wear out. Mechanical components reach the end of their useful life. Keeping the plant functional requires steady reinvestment over time. In many cities, that maintenance has been deferred because the budget could not absorb those costs.

Just as those expenses compound, growth arrives. New developments request service extensions. New ratepayers are promised. Suddenly, impact fees create an opportunity to expand the plant. Aging equipment is replaced. Capacity is added. Long-standing problems appear to be solved—once again paid for by growth.

This is not a hypothetical scenario. In Winter Garden, Florida, city leaders recently approved dramatic increases in water-related impact fees, including roughly a 330 percent increase in wastewater connection fees. The revenue is intended to fund upgrades and expansion to the city’s wastewater treatment facility. The improvements are necessary to meet regulatory requirements and accommodate growth. But the funding strategy reveals a deeper pattern. Rather than confronting years of deferred maintenance and rising operational costs through rates or long-term financial reform, the city leaned heavily on new development to finance both expansion and correction. Yes, impact fees made the upgrades possible, but they also masked an underlying issue: a system whose ongoing costs were not being sustainably funded before growth arrived—and will be even harder to sustain after expansion.

The system struggled because rates did not reflect the true cost of operating and maintaining it. Impact fees did not correct that imbalance. They merely obscured it. Now the city owns a larger, more complex, more expensive system supported by the same revenue structure that failed the original one.

Future obligations grow, hidden behind a one-time infusion of cash that made expansion feel prudent. When growth slows or maintenance cycles return, the math becomes unavoidable. This is how cities drift toward insolvency—not through recklessness, but through a series of decisions that prioritize short-term funding over long-term capacity. Impact fees allow cities to build new assets without fixing broken revenue models, expand systems they cannot sustainably maintain, and confuse growth-driven cash flow with genuine financial health.

This is the Growth Ponzi Scheme in practice: using today’s growth to cover yesterday’s obligations while creating even larger obligations for tomorrow. The system only works if growth continues—and accelerates. When it slows, the math collapses.

Though, this reality raises an important question: if cities don’t rely on impact fees, how do they pay for growth? How else do they meet new demands, expand services, or respond to increased use of infrastructure? It's a fair question, but underpinning it is the assumption that growth itself creates wealth, and that visible expansion signals financial strength. Strong Towns has long described this as the "illusion of wealth."

New buildings, new lanes of pavement, and new facilities look like progress. They create the appearance of prosperity. But appearances can be deceiving. Much of what we interpret as wealth is actually a collection of new obligations—assets that require ongoing maintenance, staffing, and eventual replacement. When those long-term costs are not honestly accounted for, growth feels like a solution when it is often just delaying the inevitable.

Impact fees reinforce this illusion. They provide a burst of cash that makes expansion feel affordable and responsible, encouraging instant action. What they do not provide is the ongoing revenue needed to sustain what has been built. The result is a system that rewards expansion while unwittingly underfunding what already exists.

Is there another way?

Instead of outsourcing financial discipline to impact fees, cities can look inward—at their budgets, capital plans, and long-term obligations—and begin by separating proposed spending into two categories.

The first is deferred needs: maintaining buildings, staffing essential services, and repairing existing infrastructure. These are not growth costs. They are obligations that were postponed. The right question is not how to pay for them now, but why they were deferred in the first place. The second is aspirational projects: new facilities, expansions, and amenities that feel urgent because growth makes them visible. These projects create new long-term liabilities. They can wait until a city has demonstrated the financial capacity to sustain them.

This shift requires patience. It requires transparency. It requires cities to understand what they can truly afford—and to recognize that they cannot build their way out of a liability.

For the past eight decades, American cities have followed a development pattern fundamentally different from the one that built towns for centuries before it. Modern development prioritizes rapid expansion, separated uses, and large upfront infrastructure investments. Success is measured by how much gets built, how fast, and how far outward services extend. What this pattern rarely measures is whether the resulting places generate enough long-term value to sustain the infrastructure they require.

Traditional, incremental development does not demand massive upfront investments. It allows places to thicken and mature over time, generating increasing value without proportionally increasing liabilities. In this pattern, cities do not rely on windfalls from growth to remain solvent. They focus on stewardship first. They fix what they own. They align revenues with responsibilities. Aspirational projects follow demonstrated strength, not the promise of future growth.

Impact fees are a rational response to a fragile growth model. But they are not a path to financial resilience. If a city cannot afford to maintain what it already owns, expanding it will not solve the problem. It will only hide it—until it becomes impossible to ignore.

.webp)