In 2022, the city of Salem, Oregon, received a $13.2 million grant from the federal RAISE program — short for Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity — to fund what was officially labeled the "McGilchrist Street Improvement Project." The project’s total cost was estimated at $28.4 million, with Salem contributing the remaining $15.2 million in local funds.

On paper, the project promised sustainability, economic development, and multimodal infrastructure. But in practice, the federal funding structure incentivized a fundamentally flawed investment in a one-mile stretch of industrial road with limited use, questionable economic potential, and a poor financial return.

This is not an outlier. It is a direct consequence of a federal transportation system that prioritizes expansion projects even when local capacity, demand, and return on investment are all absent.

Street Widening Masquerading as Progress

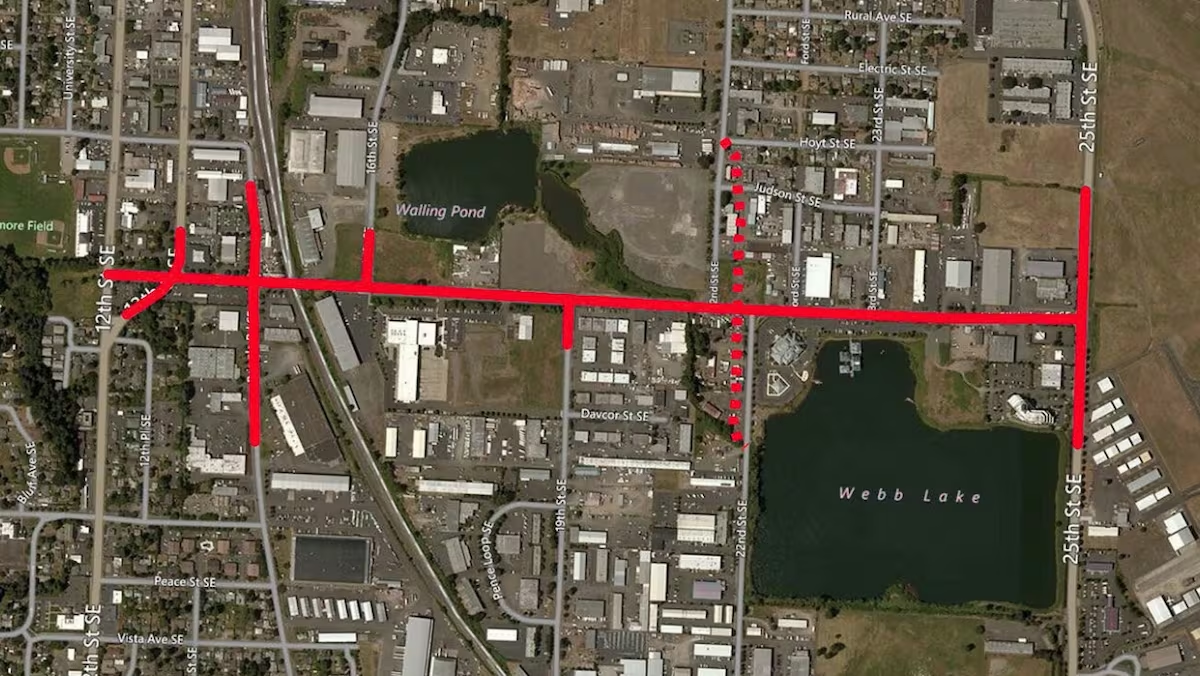

The McGilchrist project involves:

- Widening the street

- Reconstructing drainage systems

- Adding sidewalks and bike lanes

- Installing new traffic signals

These are common elements of “complete street” projects. But here, they’re being applied to an industrial corridor that currently sees just 3,600 vehicle trips per day — the kind of road one might take to reach a truck repair yard, a bar and grill, or a portable toilet rental service.

This is not a critical corridor of commerce or a growth hotspot. It is a low-intensity, low-value industrial street. Framing it as a strategic investment in sustainability or equity is misleading at best.

The language of “improvement” masks the project’s actual function: capacity expansion. The primary effect is to increase long-term public liability while offering no realistic path to a positive return.

Salem is investing $15.2 million of local funds in the McGilchrist project. The city’s own benefit-cost analysis estimates that this investment will generate $19.3 million in new property value — a projection presented with implausible precision.

Let’s assume, for argument’s sake, that this projection is correct:

- At Salem’s 1.34% property tax rate, that $19.3 million yields approximately $259,000 per year in additional tax revenue.

- At that rate, it would take 58 years to recoup the $15.2 million cost.

- If half that revenue is needed for basic public services like police, fire, and parks — as is typical — the payback window expands to 108 years.

- And when accounting for time value of money at even a modest 4% discount rate, the investment never pays back. The annual tax return doesn’t even cover the interest.

These numbers don’t reflect technical complexity; they reflect basic arithmetic. What they reveal is not just a bad project, but a local government induced to ignore obvious math in the pursuit of federal funding.

This kind of analysis is not part of the federal grant application process. In fact, it’s actively discouraged. Cities are rewarded for creating optimistic benefit-cost narratives, not for asking whether a project actually serves the long-term fiscal health of the community.

The Perverse Logic of Federal Infrastructure Funding

Why would a city like Salem prioritize such a marginal project? Because federal funding structures push them to.

To qualify for RAISE and similar programs, cities are required to demonstrate:

- High-cost, shovel-ready projects

- The potential for “transformative” impact

- A willingness to co-invest substantial local resources

This creates a system where:

- Expansion is incentivized over maintenance.

- Benefit projections are inflated to meet scoring thresholds.

- Local priorities are distorted to fit grant criteria.

- Opportunity costs are ignored in pursuit of “free” money.

Worse still, the analysis used to justify McGilchrist’s projected benefits relied on false premises: that vacant industrial parcels would redevelop to the same intensity and value as commercial lots, and that existing businesses would be replaced with higher-performing uses.

In some cases, the projections appear to double-count development that had already occurred. This is not uncommon. Because the system demands projections — not accuracy — there is no penalty for being wrong.

Without the federal grant on the table, would Salem have prioritized this project? Almost certainly not.

A financially resilient city would instead ask:

- How do we grow the tax base without dramatically increasing costs?

- What is our actual return on investment?

- Which projects yield the highest long-term value per dollar spent?

Under that lens, the McGilchrist project fails outright. The investment does not serve a critical need. It imposes long-term liabilities with no commensurate revenue. And it diverts attention and funding from higher-return opportunities in Salem’s walkable neighborhoods — places already demonstrating economic productivity and community momentum.

This is not just a questionable project. It’s the product of a funding system that rewards growth at any cost, even when the math doesn’t work and the need isn’t there.

Salem is not unique. This same pattern is playing out in cities across the country. The federal government’s transportation policy isn’t helping cities build prosperity — it’s helping them go broke, slowly and quietly, one “improvement” at a time.

.webp)