This column usually appears in early December, right as my kitchen fills with the smell of sugar and spice and the familiar rhythms of Christmas baking take over. This year, it’s appearing in mid-January instead. That’s not because I forgot, or because I lost interest. It’s because December didn’t unfold the way it normally does. The year felt unsettled right up to the end, and I never quite found the quiet moment I’ve come to rely on to take stock of what this little annual ritual is trying to tell me.

That, it turns out, is part of the story.

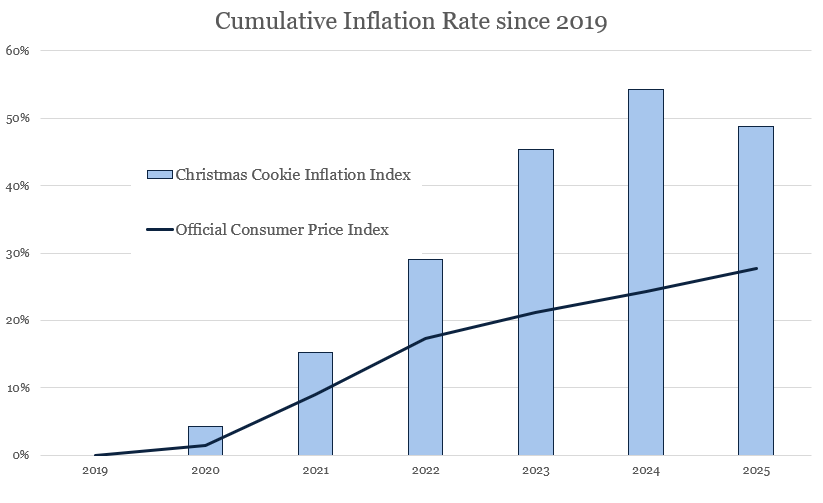

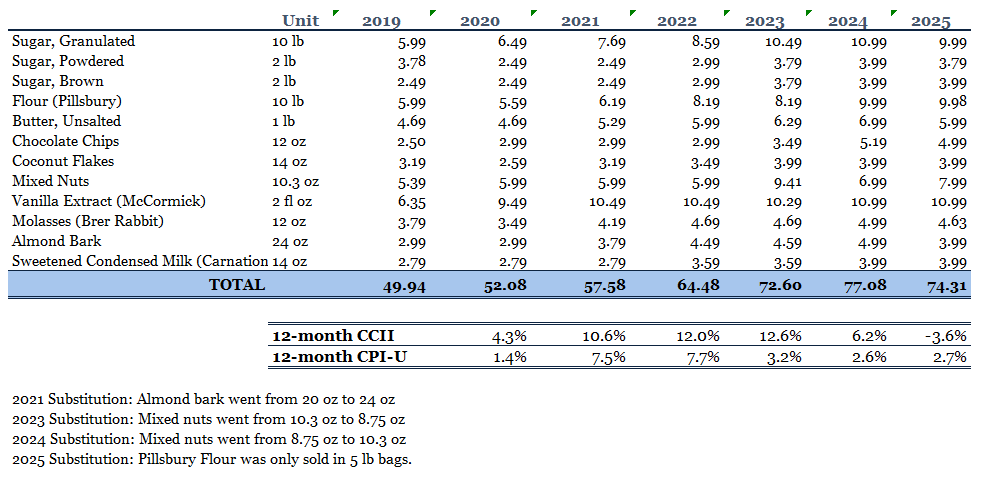

For years now, I’ve tracked what I call the Christmas Cookie Inflation Index: the price of a fixed basket of ingredients I buy every December to bake the same cookies my grandmothers made. Same recipes. Same brands. Same quantities. Same store shelves. No substitutions, no adjustments, no hedonic tricks. Just a simple record of how much it costs to carry on a family tradition.

I started doing this in 2019 because I felt something was off. Prices were rising faster than the official story said they were, and the gap between lived experience and expert assurance kept widening. Over the next several years, that intuition proved correct. My cookie ingredients went up way faster than official inflation, year after year. The index became a small, personal way of documenting a lived reality many people were told not to trust.

Until this year.

For the first time since I started tracking the Christmas Cookie Inflation Index, the number went down. Not a rounding error. Not flat. Down by 3.6 percent.

I should have felt relieved. After years of watching prices climb — sometimes sharply — here was evidence that things were getting easier, at least a little. Instead, I felt something closer to grief. The reason has nothing to do with national politics or macroeconomic theory. It has everything to do with what changed locally.

Before big-box chains dominated the landscape, Brainerd had neighborhood groceries — real ones — spread throughout the city. One of them sat across the street from my parents’ first house. I was only an infant when we lived there, and we moved when I was two, but the store remained a fixture of the neighborhood for generations. My parents shopped there, like so many others did, back when it was normal to walk to a nearby store for everyday needs. We knew the family who ran it. I graduated high school with their son, who eventually closed the store when the neighborhood grocery business finally became financially untenable.

My first real adult-ish job was at Rainbow Foods. I pushed carts and stocked shelves 30 hours a week through high school. That store sat downtown, on the former site of a historic train depot that had been torn down and replaced with a strip mall. Its existence essentially replaced the corner groceries, driving them out of business as the next new thing. Rainbow Foods survived for a good while, but it eventually closed when things shifted out to the highway bypass. Today, the building limps along with a dollar store in one corner and an auto parts shop in another. Much of it sits empty.

All of these weren’t just stores. They were employers, social infrastructure, and repositories of local memory.

After Rainbow closed, grocery shopping didn’t disappear. It consolidated. Cub Foods and Super One replaced Rainbow as the dominant big-box grocers in the area, offering larger stores, lower prices, and more convenience. Where Rainbow had once displaced the corner groceries, Cub and Super One displaced Rainbow.

Over the past year, that consolidation took its next step. Super One bought Cub. One chain absorbed the other. The number of stores went down, the number of employers went down, and the choices available to workers and shoppers narrowed. We were told this was progress, the next step in maximizing efficiency.

Before the sale, there was a prolonged labor dispute. Grocery workers — people who had shown up through the pandemic and beyond — went on strike over wages and working conditions that had failed to keep up with rising costs. Eventually, after months of conflict, a new contract was ratified. Wages went up. Conditions improved. On paper, it was a win. And then one of the stores closed.

Employees were invited to reapply for jobs at the surviving location. Some were rehired. Some were not. A close family friend — smart, capable, deeply experienced, but also a spokesperson for the union during the dispute — wasn’t chosen. She had given a significant portion of her life to that store. When consolidation came, she was no longer part of the future.

This is the context in which my grocery bill went down.

The store I now shop at is cheaper. That’s not an illusion. Anyone who lives here knows it. You can feel it in small, everyday ways: a dollar less here, a sale there. For a household under pressure, those savings matter. But cheap is not the same thing as affordable. And it is definitely not the same thing as healthy.

Lower prices came paired with fewer stores, fewer employers, less competition, less redundancy, and less local control. They came with diminished wages for some, less voice for workers, and thinner margins of care. They came after conflict, closure, and loss.

This is the part of the inflation story we almost never talk about. When systems are stressed, they don’t usually become more humane. They become simpler. Complexity — local ownership, experienced staff, long relationships, redundancy and resiliency — gets stripped away in the name of efficiency. Prices often fall after that happens, but not because the system has healed. They fall because we have shed parts of ourselves.

For years, the Christmas Cookie Inflation Index was an expression of muted outrage. It was a way of saying something is wrong, and we shouldn’t pretend otherwise, especially when people are telling us to look the other way. This year, outrage felt like the wrong response. The index didn’t contradict itself. It revealed the next phase.

Cheaper sugar came at the cost of lower wages, fewer choices, and a community with less say over its own economic life. That tradeoff may not show up in national statistics, but it shows up clearly in places like mine.

I don’t blame the workers who fought for better pay. I don’t blame the families trying to stretch their grocery dollars. I don’t even blame the companies responding to pressure by consolidating. This is how fragile systems behave under stress. Simplification looks like relief, at first.

But there is a sadness in realizing that the relief came from losing something that once mattered. Traditions depend on continuity. So do communities. When those erode, the costs don’t disappear; they’re deferred. They show up later, in quieter and harder-to-measure ways.

Cheaper prices can feel like progress in the moment, especially after years of strain. But systems that achieve affordability by narrowing choice, reducing redundancy, and squeezing out experience rarely stay cheap for long. They become brittle. They lose the capacity to adapt without breaking. What looks like savings today often becomes a larger bill tomorrow.

This year, the Christmas Cookie Inflation Index went down. And that didn’t feel like relief so much as recognition: cheap is not the same thing as affordable, and it never has been.

I’ll keep baking. I’ll keep tracking the prices. The ritual still matters. But I’m more convinced than ever that what we should be paying attention to isn’t just how much things cost today, but what kind of system we’re building to make them cheaper. And what that system will demand of us over time.