In 2001, a county commissioner named Peter McLaughlin came to my graduate transportation class to pitch a project called Northstar Commuter Rail. He was one of the central political figures behind the effort, and his presentation reflected that. He talked about coalition-building, federal funding formulas, and the work required to align the two. What he didn’t talk much about was how the system would function as transit.

At the time, commuter rail sounded exciting. I went into the class curious. I left unsettled.

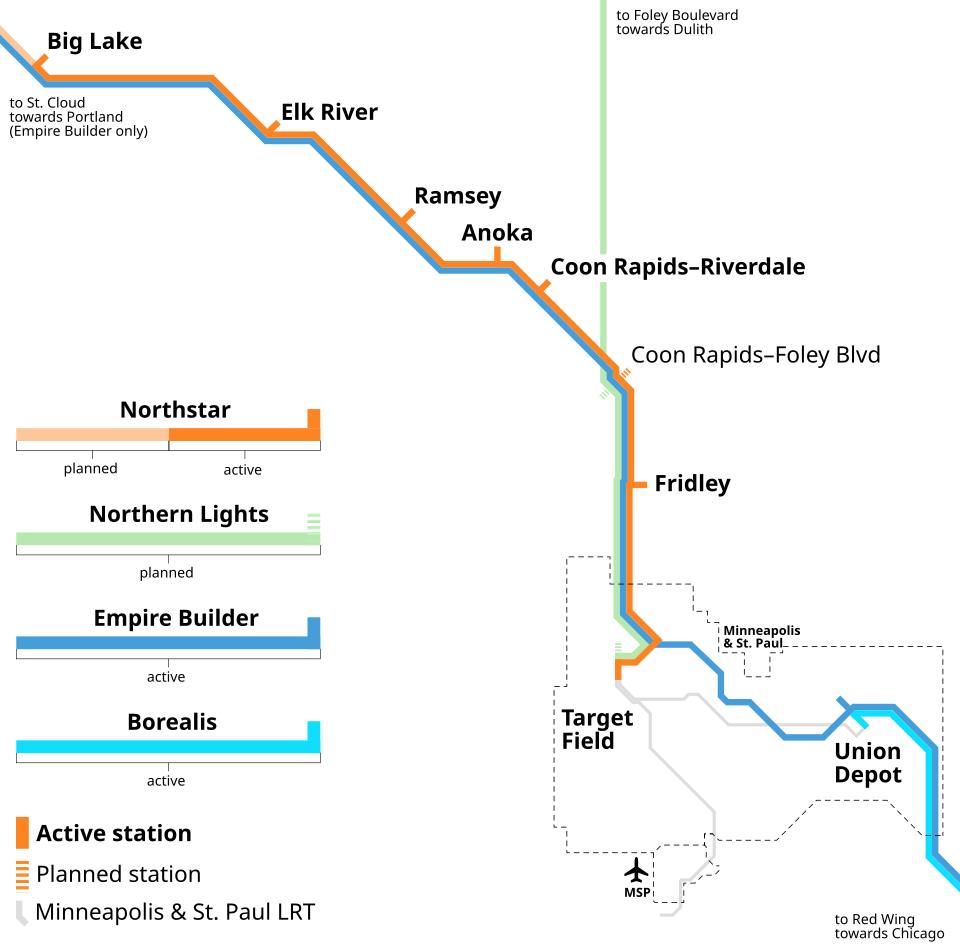

During the lecture, I asked some basic questions about viability. Why would the line stop in Elk River instead of continuing to St. Cloud, the major regional center north of Minneapolis? McLaughlin’s answer had nothing to do with ridership, service, or making the system work. It had everything to do with where the politics and the funding allowed the project to go.

This was long before Strong Towns. I didn’t yet have the framework to name what bothered me. I just knew that if the goal of the presentation was to convince me this was a good transportation project, it had the opposite effect.

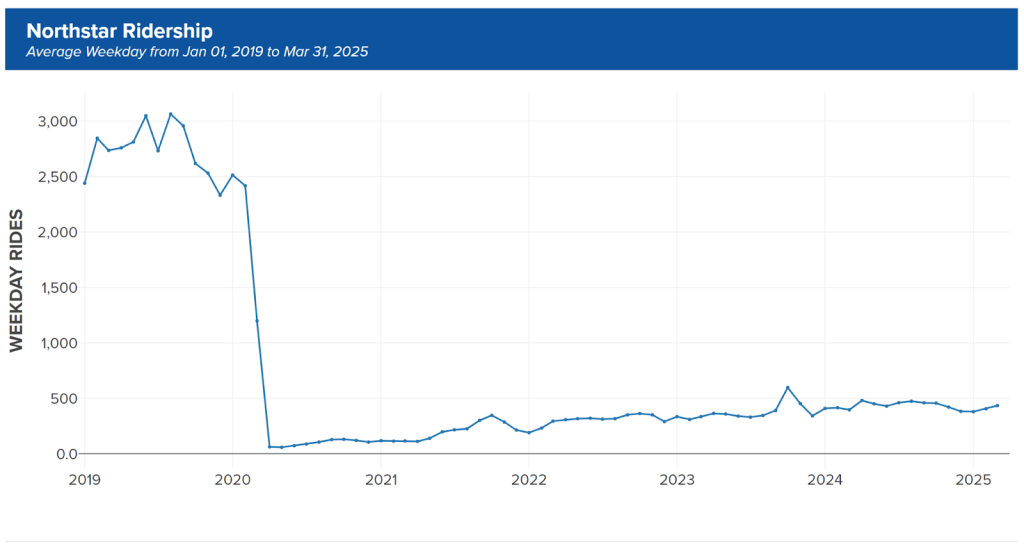

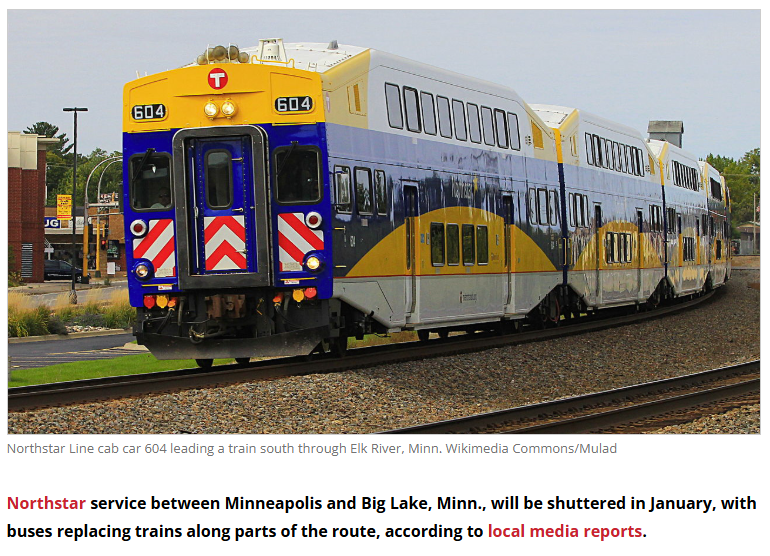

Northstar opened in 2009. Today, it’s widely regarded as a failure. Ridership never materialized as promised, service was steadily scaled back, and last month the state shut the line down, once its obligation to repay the federal government for the grant funding expired.

Most accounts of its failure focus on bad politics, insufficient commitment, or a lack of sustained funding. That framing is comforting. It suggests that, with better leadership or more willpower, things might have turned out differently.

I don’t think that’s true.

Those explanations focus on outcomes—how we failed to sustain the unsustainable—not on the decisions that shaped the project in the first place. To understand what happened, it helps to look at three decisions made early in the project’s life.

Coalition First, Transportation Second

Northstar was not conceived primarily as a transportation solution. It was conceived as a coalition. The central challenge wasn’t how to move people effectively; it was how to assemble enough jurisdictions, partners, and political buy-in to unlock federal dollars.

This is not corruption. It’s how the system works. Federal transportation funding rewards geographic distribution, partnership breadth, and political consensus. Projects that bring more players to the table are more competitive than those that are coherent but narrow.

Once coalition-building became the primary success metric, transportation logic became a constraint rather than a guide, useful only when it didn’t disrupt the coalition holding the project together.

Stations Built for Eligibility, Not Access

If you want to see what a project is optimized for, look at what gets built.

Northstar stations appeared in fields, behind big-box stores, and in locations that were functionally inaccessible to anyone not arriving by car. These were not places people were, or naturally wanted to go. They were places chosen to satisfy funding commitments.

When this contradiction was pointed out, the response was always the same: development would follow. Transit-oriented development was invoked as a future solution to present absurdities. In practice, “this will create development” became a way to backfill a narrative after the funding logic had already determined the outcome. Future development wasn’t a strategy so much as a sales pitch.

The Line Stopped Where the Funding Stopped

St. Cloud is the regional anchor. If Northstar were designed first and foremost to function as good transit, that’s where the line would have gone.

There were efforts to extend it to St. Cloud, both during its conception and later as a last-ditch attempt to keep it viable. Some legislators proposed using existing track and equipment, even suggesting reductions in service elsewhere to make the math work. Others resisted reallocating funds, insisting that any extension would require new funding and new commitments.

It’s tempting to read this as simple partisan disagreement. But both sides were operating within the same financial constraints set when the project was first assembled.

Doing the transportation-correct thing—going to St. Cloud first—broke the funding math. It unraveled the coalition. It violated the logic that made the project fundable in the first place. So the line stopped where the math stopped, not where the city did.

At this point, it’s natural to conclude that Northstar was simply a victim of bad compromises, or that it suffered from a lack of political courage. But those explanations don’t quite fit the facts.

What’s striking is not that the project couldn’t be fixed later. It’s that it was designed with the assumption that it would never need to be corrected at all.

Federal funding rewards scale. Projects grow large enough to justify national support, and that scale requires broad coalitions of backers. They are then conceived and delivered as finished systems, not as something meant to be iterated on, learned from, or adapted over time. Once built, they are too permanent to adjust, too expensive to fix, and too politically entangled to admit they need to change.

With Northstar, any attempt to improve performance meant reopening the same funding logic and coalition commitments that made the project possible in the first place. Simplifying the system meant breaking promises. Concentrating service where it would work best meant losing eligibility. Every meaningful correction required more money, more partners, and more complexity.

.jpg)

Northstar didn’t fail because we abandoned it. It failed because it faithfully followed the incentives of a federal transportation program that has long since lost its original purpose.

For most of the twentieth century, the federal transportation mission was clear: build a national highway system. That work is long since complete. The problem is that the machinery built to deliver it never shut down. Instead, it evolved into a permanent funding apparatus, one that exists to allocate money, spread political benefit, and keep projects moving.

In that system, success is measured not by outcomes, but by throughput. Not by whether a project works, but by whether it satisfies enough constituencies to justify the investment.

In effect, Northstar is not an aberration, but a textbook example of what happens when a mature federal funding system, having accomplished its original mission, repurposes itself to sustain momentum rather than value.

Which brings us to the uncomfortable conclusion: Northstar wasn’t a transportation project that failed. It was a funding project that succeeded.

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)