This is part of a short series exploring the “buttonhook” interchange at the intersection of Highways 371 and 210 in Baxter, Minnesota. Catch up with these columns:

When I wrote recently about the buttonhook interchange in Baxter, I argued that congestion isn’t the problem it’s made out to be. Wasting time is bad, but wasting lives is worse. And that’s what I want to talk about now: safety.

Early in my engineering career, I was a summer intern at the Minnesota Department of Transportation. I worked in Baxter, Minnesota, very close to where the buttonhook is now being proposed.

One day, I looked up from my cubicle and saw the district’s senior traffic engineer leaning against the wall, head down, wiping tears from his eyes. Another engineer was quietly rubbing his back to comfort him. Two grown men sharing a very emotional moment. I thought maybe someone’s spouse or child had died. Certainly, something bad had happened to someone he knew personally.

No. It turned out that another elderly woman had been killed while turning left across traffic on Highway 371 in Baxter. It happened at one of the intersections on the same corridor where the buttonhook is now proposed. I’m not sure which intersection; there are so many. And the truth is, this same scenario happened again and again during my two summers at MnDOT, and in the years I spent working at an engineering firm right next door.

I share this story to point out that, despite the anonymity of the woman involved, the engineers cared. They cared deeply. This traffic engineer was devastated, but he wasn’t an outlier. This affected everyone. It was horrible.

And it kept happening. Year after year.

Safety has been a longstanding problem along this stretch of road, and everyone at MnDOT knows it. Some of them lose sleep over it, and have been for decades. The problem isn’t a lack of concern. It’s that we’ve set engineers up with an impossible job: Make traffic fast and make access convenient, then make it all safe at the same time.

Those objectives are fundamentally in conflict. No amount of money — not even the $58 million slated for Baxter’s buttonhook — can reconcile them.

What Makes a Highway Dangerous

Highways themselves are not inherently dangerous, even with high speeds. A well-designed highway can move traffic at high speeds with relatively few crashes because the environment is simple. There are very few decisions for a driver to make. You enter, you travel, you exit.

The danger comes when speed is combined with complexity. As I wrote in "Confessions of a Recovering Engineer," this kind of corridor is “the most dangerous environment we routinely build in our cities.” It combines the speeds of a highway with the complexity of an urban street, a design that “ensures a high frequency of violent collisions.”

Cross traffic, random turning movements, vehicles stopping unexpectedly, and people trying to cross on foot; these things can all be managed safely at low speeds. They become deadly when overlaid on a corridor designed for highway speeds.

That is the exact problem on Highways 371 and 210. These roads are not designed with safety as the top priority. They are designed to serve access first, traffic speed second, and safety a distant third. We pretend that’s not the case — that we somehow prioritize safety over other concerns — but that’s obviously not true.

Take the intersection at Design Drive, which I examined in detail in my last column. That highway access is being rebuilt right now. It is literally closed to all traffic. If safety were the priority, the Design Drive access to Highway 371 would never reopen. But safety isn’t the priority; access and traffic speed are. So one of the corridor’s most dangerous intersections will soon be reopened, and — if local advocacy by the Chamber of Commerce gets its way — it will remain in place, even as traffic flows faster following the construction of the interchange.

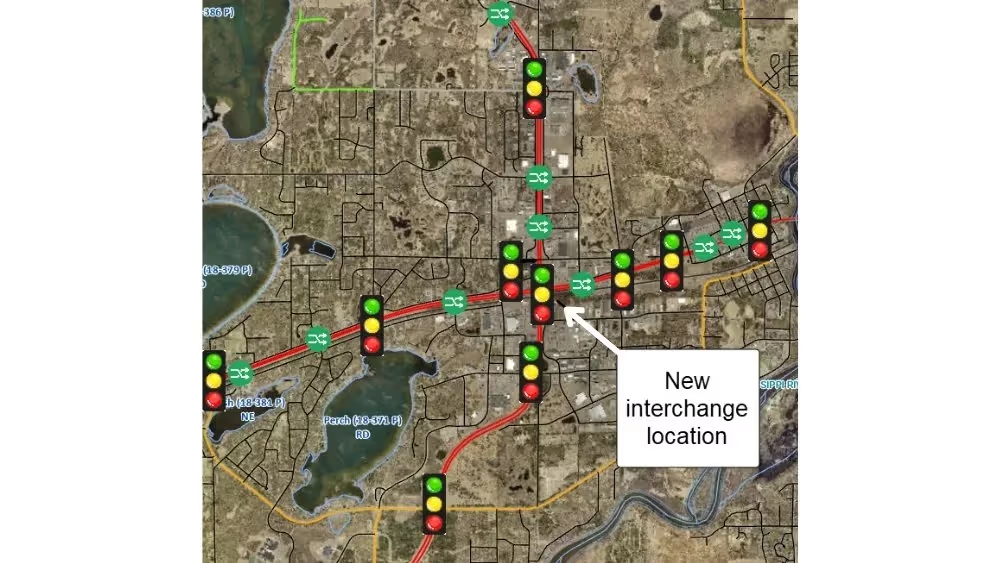

The buttonhook doesn’t fix the corridor’s safety problem because it doesn’t remove this or any of the other access points. Yes, it replaces the intersection of two highways with an interchange, but so does every version being proposed, including the single-point urban interchange (slightly modified) I’ve endorsed. What the buttonhook adds is even higher speeds heading straight into the most dangerous portion of the corridor.

How Safety Is Redefined in the City

In neighboring Brainerd, the reconstruction of Highway 210 — Washington Street to the people who live here — is scheduled to happen around the same time as the buttonhook. On paper, it should be a great opportunity for MnDOT to improve safety in the core of the city.

That’s not what’s going to happen. Once again, the priority is traffic flow, moving vehicles through faster.

The plan closes intersections throughout downtown Brainerd, something MnDOT refuses to do on Highway 371 in Baxter. It eliminates on-street parking, and it channels traffic into fewer access points, arguing that this reduces conflict and therefore improves safety. That might be true if we were talking about a highway. But this isn’t a highway. It’s a city street.

In a place like Brainerd’s downtown, where complexity is part of the fabric of the neighborhood, the way to improve safety is to slow traffic. Instead, MnDOT is setting up an environment where traffic will move faster.

What does that mean in practice? Residents on the north side of Washington Street who want to walk just a couple blocks into downtown are forced to cross a street with faster traffic — without even a crosswalk — or detour blocks out of their way to find a signalized crossing. If they do the latter, then they’ll stand and wait — in the rain, in the summer heat, or in 40-below winter cold — while through traffic gets priority.

The only outcome where the corridor becomes “safer” under MnDOT’s design is if fewer people attempt to cross it on foot or bike at all. In other words, the safety improvement comes not from fixing the design, but from discouraging people from acting like they live in a city.

What if We Were Serious About Safety?

MnDOT doesn’t have Vision Zero. What it has instead is a different slogan: Towards Zero Deaths. But what if it actually took that slogan seriously? What if, with $58 million to spend, it made safety the first and only priority?

On the bypass of 371 and 210, the department would build the simple interchange design I’ve already endorsed. Not the buttonhook, just a straightforward fix at the main intersection. Then it would close Excelsior Drive, Design Drive, and every access point from the new interchange to the fully signalized intersection at Woida Road.

Traffic would move smoothly, without random turns or unpredictable stops. And without all that complexity, crashes would all but disappear.

In Brainerd, the approach would be the opposite. If MnDOT prioritized safety over other concerns, it would dramatically slow traffic. Keep the on-street parking instead of eliminating it. Reduce the number of lanes. Add more crossing points for people walking and biking. Lean into the complexity, but at safe speeds. If a crash happens downtown, it should be nothing more than a low-stakes fender bender. That’s what Towards Zero Deaths should mean.

And here’s the thing: We could do all of this for far less than $58 million. Far less. But we won’t.

We won’t because we don’t really care about safety. At least not as much as we care about preserving access to corporate franchises in Baxter, or speeding traffic through the core of Brainerd.

The Impossible Job We’ve Given Engineers

I want to be clear: The engineers working on these projects are not villains. Many of them lose sleep over the crashes on these roads. I’ve seen it with my own eyes. They care deeply about safety. But we’ve given them an impossible job.

We tell them to make traffic fast. We tell them to make access convenient. And then we tell them to make it all safe at the same time. These objectives are fundamentally in conflict.

It’s like telling the Federal Reserve to keep inflation low while also guaranteeing full employment. These priorities conflict, and they undermine each other. That's why the definition of “priority” is singular, not plural.

You can only have one priority. For Baxter’s buttonhook interchange, that top priority is clearly not safety.

The corrupt part of this is not that the engineers don’t care about safety, but that we allow them to rationalize projects like the buttonhook as safety improvements. Yes, spending $58 million on this interchange will likely prevent some crashes. But if the objective were truly safety — if it rightly stood above all other concerns — we could prevent far more crashes, at far less expense, with a different approach.

That’s the brutal truth of the system we’ve built. I’ve often asked myself, "How many people are we willing to kill so people can get to Fleet Farm eight seconds quicker?" The answer should be zero. But it never has been. And it’s not now.

In the next column in this series, I’ll look at the “corridors of commerce” aspect of this project and show why investing in strip development in Baxter, and devaluing the neighborhoods of Brainerd, is the opposite of improving the area’s commerce.

Read the next part of this series: “The Absurdity of Highway Spending as Economic Development"

.webp)