Here’s a story you’ve probably heard before:

A new youth sports complex opens on the edge of town. Ten or twelve pristine fields. Acres of parking. A name that signals ambition… Regional, Legacy, Premier. On weekends, the place is packed with tournament traffic: minivans, tents, folding chairs, vendors. On weekdays, it sits largely empty. At the same time, closer to the city’s core, school fields are locked after hours. Park courts lack lights. Neighborhoods dense with children and young adults have no playable space within walking distance.

This coexistence (abundance on the outskirts, scarcity at the center) does not feel accidental. It’s the result of a set of incentives that consistently push cities toward large, centralized sports complexes rather than small, distributed neighborhood fields.

The question is not whether these complexes “work.” Many of them do exactly what they are designed to do. The question is what problem they are actually solving.

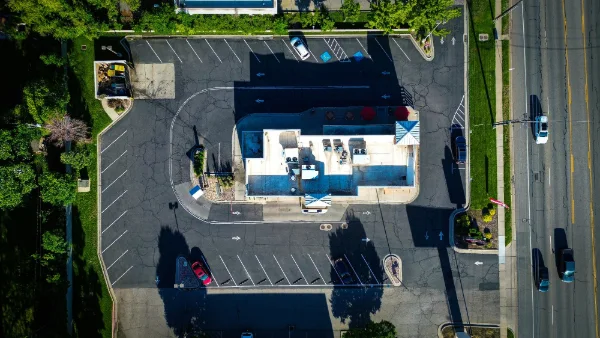

Large sports complexes are attractive to city governments because they are easy to explain. They arrive with economic impact studies attached: hotel nights, restaurant spending, regional visitors. They come with clear capital budgets, naming rights, and ribbon-cutting ceremonies. They can be photographed from the air and branded as evidence of investment. A $30 million complex feels like progress because it is visible.

Neighborhood fields, by contrast, don’t always photograph well. A lit mini-pitch on a residential block looks like maintenance instead of transformation. Ten small investments scattered across a city do not produce a single moment of political credit in the way one large facility does.

In the end, cities are not only responding to community need; they are responding to the logic of governance. Centralized projects are legible to councils, donors, and the press. Distributed infrastructure is quieter and harder to narrate. The result is predictable: cities optimize for visibility rather than proximity.

Beyond politics, sports complexes solve a series of administrative challenges. They centralize scheduling, liability, maintenance, and security. They allow recreation departments to manage sport as a contained activity rather than a diffuse one. Insurance is simpler, permitting clearer, and staff can be concentrated in one place.

Neighborhood fields demand something different. They require tolerance for informal use. They require shared ownership and ambiguity. They invite unscheduled play, mixed ages, and overlapping activities. They make risk harder to quantify and control.

Over time, American cities have made a quiet tradeoff: In the name of safety, efficiency, and liability management, they have narrowed the conditions under which play is allowed to happen. Locked school fields are the clearest example. Publicly funded land—arguably the most evenly distributed athletic infrastructure in the country—is increasingly inaccessible outside of sanctioned hours for certain groups. What once functioned as a neighborhood commons now operates as a reserved facility.

This is not some sort of conspiracy; it is a cumulative effect of policy choices that privilege order over use. In any case, the outcome is the same: informal play disappears, not because people stopped wanting it, but because cities stopped permitting it.

Sports complexes are often defended as “for the kids”, which is true, but incomplete. They are for a specific kind of kid: one whose family has transportation, flexible weekends, and the means to pay tournament and registration fees. They are for teams already inside organized systems.

A facility located thirty minutes from most neighborhoods, designed around weekend tournaments, implicitly excludes:

- children who rely on public transit

- adults who work nonstandard hours

- people seeking casual, after-work play

- families for whom sport is not a full-time logistical project

By contrast, neighborhood fields, especially when lit and unlocked, serve a much broader population. They support:

- spontaneous play

- intergenerational use

- adult recreation

- repeated, low-pressure participation

The difference is not simply access, but frequency. A child who can play three nights a week within walking distance accumulates far more meaningful engagement than one who plays once a week at a distant complex.

Complexes maximize peak usage. Neighborhood fields maximize lifetime usage. Cities tend to choose the former.

One reason this pattern persists is scale. A single large complex carries a large price tag, which paradoxically makes it easier to justify. It feels like a serious investment and a line item that commands attention. Distributed infrastructure does not. Ten $1 million neighborhood projects feel incremental rather than transformative, even if they serve more people more often. Maintenance budgets are harder to celebrate than capital expenditures.

Yet from a public-health and civic perspective, the return on neighborhood infrastructure is often higher. A small field used daily by dozens of people across age groups produces more cumulative hours of movement, social contact, and belonging than a complex used intensely but intermittently. The problem is not that cities lack resources. It is that they measure success at the wrong scale.

This is not an abstract critique. Other cities offer concrete alternatives. In the Paris suburbs, municipal pitches are embedded directly into residential neighborhoods. These are not elite facilities. They are durable, visible, and permissive. Community tournaments like the Coupe d’Aulnay use public fields to create large-scale civic events without privatizing space. In Medellín, small neighborhood courts—canchas de barrio—were built deliberately as tools of violence reduction and social cohesion. Lighting, visibility, and accessibility mattered more than surface quality. These spaces became anchors of daily life, not destinations.

Even within the United States, basketball provides a telling comparison. For much of the twentieth century, cities invested heavily in outdoor courts. These were cheap, ubiquitous, and politically uncontroversial. They produced a culture of pickup play that persists decades later. Basketball did not become a public language because of professional leagues alone. It became a public language because cities made it unavoidable.

Soccer, by contrast, was routed into complexes and clubs. This difference was not inevitable. It was designed. So… what would change if cities asked a different question?

Instead of: How do we host more tournaments?

Ask: Can a twelve-year-old play within a ten-minute walk of home, three nights a week?

Instead of: How do we attract regional events?

Ask: Where do adults play after work without registering, paying, or driving across town?

These questions point toward a different set of investments:

- lighting instead of fencing

- unlocked gates instead of reservation systems

- durable surfaces instead of showcase turf

- policy that tolerates informal use rather than suppressing it

The most powerful sports infrastructure is not the kind people travel to; it’s the kind they stop noticing because it is always there.

Cities keep building sports complexes not because they are the best way to create access, but because they are the easiest way to demonstrate investment. They are legible, controllable, and photogenic. Neighborhood fields are none of those things. They are messy. They are dispersed. They blur the line between program and public life... But they do something complexes cannot.

They turn play into a daily practice rather than a scheduled event. They allow sport to function as civic infrastructure rather than consumer experience. American cities do not lack ambition when it comes to sports. They lack imagination about scale.

Ultimately, the choice is not between excellence and access. it's between building for moments and building for lives. If cities want sport to serve public health, belonging, and community—rather than only weekends and tournaments—they will need fewer showcases and more spaces where nothing is scheduled, and everything is possible.

[[divider]]

This article was originally published, in slightly different form, on Noah Toumert's The People's Pitch. It is shared here with permission.

.webp)

.webp)